Stars and bars (combinatorics)

In the context of combinatorial mathematics, stars and bars is a graphical aid for deriving certain combinatorial theorems. It was popularized by William Feller in his classic book on probability.[1]

Contents |

Statements of theorems

Theorem one

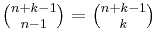

For any pair of positive integers n and k, the number of distinct n-tuples of positive integers whose sum is k is given by the binomial coefficient  .

.

Theorem two

For any pair of natural numbers n and k, the number of distinct n-tuples of non-negative integers whose sum is k is given by the binomial coefficient  , or equivalently by the multiset number

, or equivalently by the multiset number  which counts the multisets of cardinality k, with elements taken from a set of n elements (for

which counts the multisets of cardinality k, with elements taken from a set of n elements (for  both these numbers are defined to be 1).

both these numbers are defined to be 1).

Proofs

Theorem one

Suppose one has k objects (to be represented as stars; in the example below k = 7) to be placed into n bins (in the example n = 3), such that all bins contain at least one object; one distinguishes the bins (say they are numbered 1 to n) but one does not wish to distinguish the k stars (so configurations are only distinguished by the number of stars present in each bin; in fact a configuration is represented by a n-tuple of positive integers as in the statement of the theorem). Instead of starting to place stars into bins, one starts by placing the stars on a line:

|

where the stars for the first bin will be taken from the left, followed by the stars for the second bin, and so forth. Thus the configuration will be determined once one knows what is the first star going to the second bin, and the first star going to the third bin, and so on. One can indicate this by placing n − 1 separating bars at some places between two stars; since no bin is allowed to be empty, there can be at most one bar between a given pair of stars:

|

|||||

| Fig. 2: two bars give rise to three bins containing 4, 1, and 2 objects |

Thus one views the k stars as fixed objects defining k − 1 gaps, in each of which there may or not be one bar (bin partition). One has to choose n − 1 of them to actually contain a bar; therefore there are  possible configurations (see combination).

possible configurations (see combination).

Theorem two

If  , one can apply theorem one to n + k objects, giving

, one can apply theorem one to n + k objects, giving  configurations with at least one object in each bin, and then remove one object from each bin to obtain a distribution of k objects into n bins, in which some bins may be empty. For example, placing 10 objects in 5 bins, allowing for bins to be empty, is equivalent to placing 15 objects in 5 bins and forcing something to be in each bin. An alternative way to arrive directly at the binomial coefficient: in a sequence of

configurations with at least one object in each bin, and then remove one object from each bin to obtain a distribution of k objects into n bins, in which some bins may be empty. For example, placing 10 objects in 5 bins, allowing for bins to be empty, is equivalent to placing 15 objects in 5 bins and forcing something to be in each bin. An alternative way to arrive directly at the binomial coefficient: in a sequence of  symbols, one has to choose k of them to be stars and the remaining

symbols, one has to choose k of them to be stars and the remaining  to be bars (which can now be next to each other).

to be bars (which can now be next to each other).

The case n = 0 (no bins at all) allows 0 configurations, unless k = 0 as well (no objects to place), in which there is one configuration (since an empty sum is defined to be 0). In fact the binomial coefficient  takes these values for n = 0 (since by convention

takes these values for n = 0 (since by convention  (unlike

(unlike  , which by convention takes value 0 when

, which by convention takes value 0 when  , which is why the former expression is the one used in the statement of the theorem).

, which is why the former expression is the one used in the statement of the theorem).

Example

For example, if k = 5, n = 4, and a set of size n is {a, b, c, d}, then ★|★★★||★ would represent the multiset {a, b, b, b, d} or the 4-tuple (1,3,0,1). The representation of any multiset for this example would use 5 stars (k) and 3 bars (n − 1).

Seven indistinguishable one dollar coins are to be distributed among Amber, Ben and Curtis so that each of them receives at least one dollar. Thus the stars and bars apply with n = 7 and k = 3; hence there are  ways to distribute the coins.

ways to distribute the coins.

References

- ^ Feller, W. (19f50) An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications, Wiley, Vol 1, 2nd ed.

Other Sources

- Pitman, Jim (1993). Probability. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-97974-3.